1. Introduction

You are in east Africa. (Or northern Brazil, southeast Asia, the USA Midwest, wherever.) A church is considering a man for "over-seer" or "super-visor" (epi-skopos), "elder" (presbyteros), "pastor" (poimēn). (Those are the same role in their tradition.)[1] Let's call him Adroa.

Adroa is honest, self-controlled, and respectable. He's a sound leader in his household. He fits all the qualifications in 1 Tim 3—except he is a terrible teacher. When he teaches or preaches, the locals cannot follow him. His mentoring influence and leadership in Christ feature prominently in many testimonies, but he's a bad teacher. Not false, mind you; just bad.

If he cannot teach, should Adroa be an overseer? (An elder? A pastor?)

Many people (including me previously) respond, "Obviously not, for 1 Tim 3:2 says clearly that 'the overseer must be . . . able to teach' (ESV, NIV), 'apt to teach' (KJV), 'an apt teacher' (RSV)." Such discussions follow: "Well, how 'able' must he be?" "Is there a 'low bar'?" "What forms of communication can we argue are 'teaching'? Only in front of a congregation or crowd (of what size)? In a small group? One-on-one at a dinner table or café? Any verbal communication?"

Such discussions actually point us in the wrong direction—exegetically, theologically, and practically. In this article I will point us in what I think is Paul's direction, arguing for two interwoven ideas:

1. we should translate Paul's adjective didaktikos in 1 Tim 3:2 as "didactic," not "able to teach"; and

2. we should unpack Paul's meaning as having a character actively oriented toward over-seeing the teaching that is happening in the community, even when not doing any teaching himself.[2]

First, we will explore who did teaching within Pauline circles (§2). We will then explore what Paul likely meant by "didactic" within his context (§§3–4). Finally, I will use a few Pauline texts associated with 1 Tim 3:2 (such as Titus 1:9) to prompt practical ideas for Adroa's church—and beyond (§5).

2. Who Did the Teaching in the Pauline Circles?

Tangled around the phrase "able to teach" in 1 Tim 3:2 are myriad assumptions, convictions, and traditions about "overseers" ("bishops"), "elders," "pastors," "teachers," "teaching," "preaching," etc. in literature, ordaining bodies, and churches. We begin untangling these by exploring who was meant to do teaching in Pauline circles. Healthy teaching was crucial to Paul's vision and mission; he saw teaching interwoven throughout the fabric of the Christian community.[3]

Most broadly, "the word of Christ" must "dwell richly" among the saints as they "teach" and counsel each other in all wisdom (Col 3:16). Concretely, Paul was delighted that Timothy "learned" the Jewish Scriptures from his grandmother Lois and mother Eunice, for their biblical training primed Timothy to respond wisely when Jesus was proclaimed (2 Tim 3:14–15; cf. 1:5). Paul gives evidence of numerous unnamed people "teaching" throughout the Christian community (Eph 4:14; 1 Tim 6:3; 2 Tim 2:2), and his wording suggests that such activity itself was not the problem; rather, the reason to stop one of them from teaching was if their message was false.[4] Likewise, Paul wants Titus to urge older Christian women in Crete to continue their "good teaching" of younger women (Titus 2:3). Teachers seem to be everywhere in early Christian communities.

Beyond that broadest sense that every saint should be "teaching" one another, God also distributes specific gifts among his people: gifts as diverse and community-edifying as serving, urging, contributing, leading, showing mercy, prophesying (even distributed diversely: e.g., to old men, young men, manservants, maidservants, Agabus, Philip's four daughters, the men and women of 1 Cor 11), and "teaching" (Rom 12:6–8). Paul's dear co-worker, Priscilla, alongside her husband Aquila, may have had a particular gift in teaching; even if not, she (and Aquila) took seriously her (their) general Christian responsibility to give better theological education to the teacher and apologist Apollos (Acts 18:26).[5]

Within the church, God establishes "teachers" as third alongside apostles and prophets (1 Cor 12:28–29) as well as "teaching" alongside other speaking gifts (14:6).[6] Even Paul himself was only one of "many" teachers and prophets in Antioch early on (Acts 15:35) beyond those named with him (13:1). Indeed, the enthroned Christ "gives" to the church not only the apostles, the prophets, and the evangelists, but specifically "teachers," whom Paul sets in close connection with the pastors yet as a recognizably distinct group from them (Eph 4:11).[7]

So, who did teaching in Pauline communities of faith? All the saints, particular saints with a Spiritual gift of teaching, and "teachers." But even they were not the only ones doing so, at least in Ephesus. Paul describes (not prescribes) to Timothy how some "elders" (presbyteroi) in Ephesus were actively "laboring in word and teaching" (1 Tim 5:17b). Paul commends those particular elders as especially worthy of double honor.[8] (Notice that Paul does not command that all elders or even any elder must be such a laborer, especially if Jesus has not decided to gift any elders in a given location as teachers.) The other Ephesian elders in Timothy's day were "leading," "directing," "ruling" (proistēmi) without laboring in word and teaching, and Paul still doubly commends those doing it well (5:17a). While Paul's words in 1 Tim 5:17 are descriptive (not prescriptive), and commending (not commanding), Paul's wording to the Ephesian elders in Acts 20:28 does carry a weight for an elder's role beyond mere description and commendation: God actually made the Ephesian elders (presbyteroi) to be "overseers" (episkopous) who were "to pastor" or "shepherd" (poimainein)—with no coordinate command to teach. Why? Well, God raises up teachers in addition to pastors/overseers/elders.[9]

In light of the breadth of "teaching" and "learning" meant to happen in Christian communities—e.g., all the saints, many teachers (as long as their content remains healthy), whomever is Spirit-gifted as a teacher, etc., in addition to some of the elders in Ephesus—the early Christian community was very much a "learning community" as well as a "worship community."[10] Teachers and teaching were ubiquitous in Pauline circles. The teaching was not necessarily done by any of the overseers/elders/pastors, though it certainly was under their super-vision (epi-skopos). This is why Paul explains to Timothy that an overseer must be "didactic" (didaktikos; 1 Tim 3:2).[11]

3. Doesn't Paul Say That Overseers Must Be "Able to Teach"?

In 1 Tim 3:2, doesn't Paul outright say overseers must be "able to teach" as a requirement? I mean, sure, not all leaders must be skilled or gifted at teaching (though many have interpreted didaktikos as such),[12] but all must at least be able to teach in some weaker sense—no? Someone might say, "I am not good at playing football (soccer), but I am certainly able to swing my foot and kick the ball . . . -ish." So, too, with overseers and teaching—right?

3.1 Discussions of "Ability" Point in the Wrong Direction

This is where many churches, ordaining bodies, seminary professors, and seminary students start wondering how poor someone (like Adroa) "can" teach for us to still say "Well, at least he is 'able.'" Discussions of a "low bar" arise here. Some begin playing fast and loose with the idea of "teaching," trying to argue what forms of communication could possibly be labelled "teaching." Why? Because if such-and-such could be considered "teaching," and if such-and-such might be the "low bar," then we could consider Adroa (or whomever) "able"—even if just barely—to "teach"—if we squint just right. Then we can appoint Adroa (or whomever) an overseer, elder, pastor.

That whole mindset misses Paul's point with the adjective he uses. What's more, that mindset sends search committees or boards or congregations or seminaries or students in the wrong direction regarding overseers, elders, pastors. So, what is the correct direction?

3.2 What "Didactic" Might Mean—More Options

Firstly, and at a merely surface level, the word "able" is not in the Greek in 1 Tim 3:2. The overseer must simply be didaktikos. English has this adjective too: "didactic," though "didactic" may not be even as flexible as didaktikos. That is why I'll unpack what I think Paul means by "didactic."

Paul certainly can use the explicit wording of "ability," including in these very letters to Timothy.[13] Christ "is able [dunatos] to guard my deposit until that day" (2 Tim 1:12). Timothy's Scriptures (our OT) are "the things that are able [ta dunamena] to make you wise into salvation through faith in Christ Jesus" (2 Tim 3:15). Paul writes to Titus about the elders (1:5) that the overseer (1:7) must "be able [dunatos] to urge [them] in the healthy teaching and to convict the naysayers" (Titus 1:9; see §5.2 below). In 1 Tim 3:2, though, Paul does not write "able to teach," such as dunatos didaskein. He simply uses an adjective: a church overseer or supervisor (epi-skopos) must be "didactic" (didaktikos).

But surely, we might think, it's obvious what "didactic" means. A "didactic" person is someone who can and does teach—right? Even if skill or gifting is not necessary, surely a "didactic" person must have a bent or orientation toward doing teaching—right?[14]

Suppose I tell you my father is "didactic." You might (naturally) envision him constantly teaching us kids. When writing about 1 Tim 3:2, Christopher Hutson uses the helpful analogy of a father in the Greco-Roman world. He writes, "A primary responsibility of a father was to attend to the education of his children."[15] Hutson's comparison is socially and culturally apt, for Paul sees overseers and elders (add pastors if you'd like) like a father or house-manager who leads, rules, directs and cares for God's household family (1 Tim 3:4–5; cf. Titus 1:5–7). Hutson's language of "attend to the education" is even helpful. But Hutson leads us down only one path to understanding how a father might "attend" to his children's education: the father personally teaches his kids.

There are two chief errors here. Firstly, that is not the only way to think about the adjective "didactic." Secondly, and more importantly, that is not the most historically accurate way to think of a father's relationship to his children's education in Paul's culture.[16]

For example, Paul himself discusses children being put under a paidagōgos, a "child-leader," a guardian (Gal 3:24–25). The pedagogue was supplied by a father who cared about and was "attending to" the son's education.[17] Pedagogues would escort the son to school, over-see them there, and generally care for the son's physical and moral (and sometimes linguistic) development.[18]

Re-imagine my father as "didactic" in Paul's Greco-Roman context: he would be continuously engaged in vetting our schools and teachers as well as our pedagogues. Even if my father was not doing any of the teaching himself, we would rightly call him "didactic" in orientation to his household—i.e., actively attending to the education of those therein.

Discussions about didaktikos tend to bounce back and forth between whether a person is (1) able to do teaching ("able to teach") or (2) able to be taught ("teachable").[19] Yet in the ancient evidence we have that is closest in time and culture to Paul—to which we will now turn (§4)—the adjective "didactic" is not used of the person doing the teaching, and it is not used of the person being taught. There is a third option, and it accords well (not directly, but well) with the idea of a father didactically overseeing the teachers and pedagogues who do the education of his sons.

4. What Did "Didactic" Mean in Paul's Day?

When wondering what a word meant in Paul's day, we tend to open up a lexicon. So doing, it will seem a "no brainer" that in the first century didaktikos meant something like "able to teach,"[20] "apt at teaching,"[21] "qualified to teach,"[22] "skillful in teaching,"[23] "competent to teach,"[24] etc. And who are we to question lexicons?! But these resources give no reasoning for interpreting didaktikos as they do. Neither do some grammars.[25] Other grammars, though, do give some reasoning. Analyzing their logic for interpreting didaktikos as "able to teach" will help us polish our lenses, so to speak (§4.1), so that we can look more clearly at the ancient evidence itself from a bit after Paul's day (§4.2) and in Paul's own day (§4.3).

4.1 Our Grammatical Preconceptions When Seeing the Ancient Evidence

What various grammars and lexicons say (and what commentaries repeat) colors our lenses about what -ikos adjectives must mean. For example, William Chamberlain presented in his 1961 An Exegetical Grammar of the Greek New Testament what the various adjective endings suggest about their meaning: e.g., -ios means possession or belonging to; -inos means material; -ikos (which is where our word didactikos fits) means "ability or fitness."[26]

Sometimes this fits: e.g., xylinos from xylos (wood) means "made of wood" or "wooden," i.e., material. Sometimes this does not fit: e.g., Paul uses choikos from choos (dust) rather than choinos to convey how Adam was made out of the material of dust (1 Cor 15:47). No, Paul is not saying or implying from his use of the -ikos suffix that Adam was "able to dust" or even "fit for dust." (Adam being fit to return to dust is theologically true enough, but in 1 Cor 15 Paul is focused on his creation out of dust.)

In fact, in 1 Cor 15:42–49 Paul uses a cluster of fascinating -ikos adjectives, none of which convey ability. Psychikos does not mean "able to soul." Pneumatikos does not mean "able to Spirit." Sarkikos does not mean "able to flesh." This makes me wonder: does Paul have a pattern of using -ikos adjectives that does not fit Chamberlain's categories?

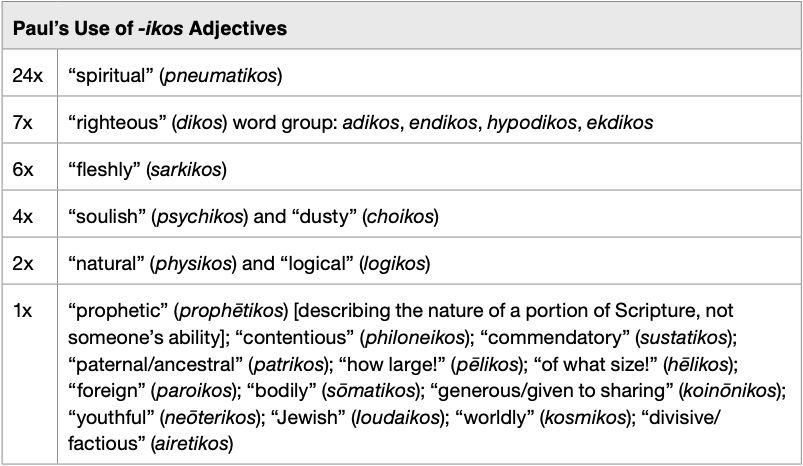

Setting aside "didactic" for the moment, look at Paul's -ikos adjectives:

Notice that none of Paul's uses of -ikos adjectives have to do with ability (much less skill).

Notice that none of Paul's uses of -ikos adjectives have to do with ability (much less skill).

However, that observation does not automatically mean that didaktikos does not imply ability. The Greek adjective "didactic" could, in theory, inherently contain the idea of ability even while none of Paul's other -ikos ending adjectives does. Does it?

The adjectival form didaktikos might be derived from the verb didaskō rather than from a noun.[27] If so, it is unlike "soulish" (psychikos) derived from soul (psychē), "spiritual" (pneumatikos) from spirit (pneuma), etc.—all of which are derived from more static nouns. If so, didaktikos might inherently carry a more active sense than the other -ikos adjectives that Paul uses that are derived from nouns.[28] Moulton and Howard argue that -ikos adjectives in general do tend to have a "verbal force strongly present."[29] (But this is not true of most or all of Paul's 65 uses.) How much more might a verbal force be true of -ikos adjectives derived from verbs?

Pause. Where do these insights actually get us? Consider two points. First, do not confuse activity with ability; they are not the same thing. Second, do not limit activity to personally doing. Remember my Greco-Roman father actively attending to our education while not doing the teaching. If we keep ourselves from these two erroneous assumptions, we will see more clearly how the ancients actually used the word.

We should set aside any fixed assumption of ability for Paul's uses of -ikos adjectives. But what about "fitness"? Chamberlain wrote "ability or fitness."[30] Does "fitness" work within Paul's usage?

For example, Paul called Adam's created body a psych-ikon body and Jesus's resurrected body a pneumat-ikon body. He obviously did not mean that they were "able to soul" and "able to Spirit," respectively; but did Paul consider Adam's body to be created "fit for a soul" and Jesus's body to be resurrected "fit for the Spirit"? This may make some theological sense, broadly speaking. It does not make exegetical sense here: Paul calls Adam's created body "soulish" due to Gen 2:7 in which Adam "became a living soul" (body + breath = living soul); he was made to be a living "soul," not made to receive a "soul."[31]

But again, where would "fit for" actually get us with regard to didaktikos anyway? Overseers must be "fit for teaching," but in what way? Fit to receive teaching? Fit to do teaching? What about fit to oversee others' teaching? We are back to precisely why we need this present study to explore how didaktikos was used in Paul's day.

Here is one final thought to clear our lenses before looking at the ancient uses of didaktikos. Herbert Smyth's 1920 Greek Grammar adds that -ikos adjectives may denote "relation" more than "fitness or ability."[32] "Relation" is an interesting category. Moulton and Howard add that early on the -ikos suffixes on adjectives tended to carry a prominent meaning of "pertaining to" or "with the characteristics of."[33] An overseer must be characterized by teaching, must pertain to teaching, must be related to teaching? Yes, but whose teaching? His own? That of others within the community of faith?

This is precisely where a recent study by Paul Himes on didaktikos in the ancient world (though post-Paul) has offered some helpful engagement with primary ancient literature (§4.2). That said, he leaves the gap in evidence and reasoning that I am filling in (§4.3).

4.2 Uses of "Didactic" in the Ancient World Post-Paul

Himes helpfully explores "didactic" in ancient literature in his 2017 article aptly entitled "Rethinking the Translation of διδακτικός in 1 Tim. 3:2 and 2 Tim. 2:24."[34] In our extant literature, we only know of four uses of didaktikos before Paul's two. Each of those four are in Philo of Alexandria (c. 20 BCE–50 CE), a Jewish commentator on the Pentateuch before and during Jesus's and Paul's day.[35] Philo's four uses of "didactic" are historically important, though Himes does not think so. This is the crucial weakness in his otherwise solid study. We will turn to Philo's uses of the adjective below (§4.3). First, though, what has Himes demonstrated about the uses of "didactic" in the ancient world after Paul?

Himes points us to three uses of didaktikos by Sextus Empiricus, who probably lived in the second or third century after Christ[36] and who provides us with our only extant (by 2017) secular use of the adjective "didactic" pre-3rd century CE. Other uses are in Christian circles. One is possibly by Ignatius (d. 108/140 CE). One is by Clement of Alexandria (c. 150–215 CE), who is actually commenting on one of Philo's uses. Four are by Origen (c. 185–253 CE). Since word nuances and even meanings can easily shift within one or two centuries, we must be cautious about anachronism when considering the later evidence. Fortunately, Himes is fairly careful.

Clustered around the second and third centuries CE, didaktikos can refer to activity in teaching or activity in being taught. Himes observes that neither of these really implies ability or skill, though, so "able to teach" is not a good translation. For example, according to Himes, Origen does not (or does not necessarily) mean or even imply ability or skill when he uses "didactic." Origen inserts "didactic" into Titus 1:9 to refer to "the teacher" (ton didaskalon) who not only "is able to convict the opposers" but also who himself "has been instructed" (pepaideumenous) (Against Celsus 3.48). Origen has left out Paul's reference to the overseer's role in being able to urge people in the healthy teaching (perhaps in the healthy teaching of others). For Himes, Origen's use of "didactic" means not that the overseer must have an ability to teach; more generally, the overseer "ha[s] to do with" or is "characterized by" teaching.

In Ignatius's "Longer Recension" (possibly spurious), the author quotes 2 Tim 2:24 in which the Lord's slave must be, among other character qualities, didaktikon. Ignatius writes:

The Lord's slave must not be quarrelsome but rather gentle toward everyone, didactic [didaktikon], patient with what is bad, in consideration instructing [paideuonta] those who set themselves against (2 Tim. 2:24–25).

While Himes rejects the translation of didaktikos as "teachable" for Paul (just as he also rejects "able to teach"), he nevertheless believes that due to the way Ignatius uses the term, "context might actually support 'teachable'" here.[37]

Clement of Alexandria refers to Philo of Alexandria's use of didaktikos when writing about the Sarah-Hagar narrative (see Philo's use below). Clement follows Philo in calling wisdom didaktikē—i.e., Wisdom is didactic. Like Philo, Clement does not mean by this phrase that she is the teacher. Wisdom is not characterized by doing teaching here. Clement also does not mean that Wisdom is being instructed—so not "teachable." There appears to be a third category.

Finally, the Skeptic Sextus Empiricus explains in Outlines of Pyrrhonism that certain definitions of objects cannot be "apprehensive and didactic" (2.210). They cannot be known (apprehended) or taught in the way the Dogmatists are attempting. It is not as though the objects are "didactic" in that they are "able to teach" or even doing teaching. They are also not themselves "teachable." They are in that third category: more generally connected to teaching. Finally, in Book 11 "Against the Ethicists" of his Against the Mathematicians, Sextus notes how a wise person really cannot be "didactic" of an unwise person since wisdom cannot know unwisdom (11.245). Here "didactic" does seem to have the sense of actively doing teaching, though still not connoting ability or skill.

One- to two-hundred years after Paul, according to Himes, the adjective "didactic" did not usually—and never clearly—mean "able to teach." There was actually a third category that we don't tend to consider in which the "didactic" one is neither the teacher nor the student.

How was "didactic" used just before or in Paul's day? Surely that would be important to know, especially if used by a fellow Jewish interpreter of the same Scriptures (our OT).

4.3 "Didactic" in the Ancient World in Paul's Day

English dictionaries like Merriam-Webster explain that "didactic" comes from the Greek didaktikos and the verb didaskein, "meaning 'to teach'," and thus "something didactic does just that: it teaches or instructs."[38] But this is not actually true of our closest historical data to Paul—namely, Philo's four uses of didaktikos.

In his commentary on Gen 16:1–6, Philo discusses "the didactic virtue" (hē didaktikē aretē). He uses the feminine form of the adjective "didactic" since "virtue" is a feminine noun, but it is the same adjective Paul uses. Philo compares three ways to acquire virtue:

1. "the didactic virtue" (hē didaktikē aretē), which is taught to people by someone;

2. "the virtue perfected through practice" (hē di' askēseōs teleioumenē), which consists of various doctrines and dogmas to practice with labor; and

3. "the self-discipled kind" (to automathes genos), in which one perseveres in training oneself

(Cong. 35–36).

Philo's label "didactic virtue" means it is obtained by teaching. It is significant that the "didactic" virtue is not doing any teaching, and neither is it being taught something. It is the third type—which Clement (who got it from Philo) and Sextus Empiricus would later use. We might say that virtue is "didactic" in that it is generally associated with or characterized by teaching—but not by doing teaching (whether "able" or not) nor by receiving teaching (as if teachable).[39]

Philo's other three uses of "didactic" are similar. In On the Change of Names, which is his commentary on Gen 17:1–22, Philo again writes about how "the didactic virtue" differs from "the virtue gained by labor" (Mut. 83–88, cf. 255). The person who acquires "the didactic virtue" is "one who by teaching has been improved." Again, the one with the adjective "didactic" attached to it (virtue) is not the one doing the teaching, neither is it the one being taught something. To be "didactic" is, again, more simply to be generally associated with or characterized by teaching without doing it or receiving it.[40]

For Philo, both forms of virtue—i.e., the one being taught to someone and the one acquired through labor—are again contrasted with the kind of virtue that is acquired by "self-teaching" (autodidakton) and "self-discipling" (automathes) (§88). Thus, while Philo can obviously use the "didak-" word group about actively doing teaching (-didakton here)—which no one claims is not the case—that is not what Philo means by the adjective "didactic" in any of his uses of the adjective.

I will summarize and begin to move toward Paul—though carefully. For Philo, Person X teaches virtue to Person Y, and Philo calls the virtue "didactic." This use obviously has a difference from Paul's use: i.e., while Philo says that Person X teaches a "didactic" thing to Person Y, Paul is not saying that Person X teaches the "didactic" overseer to Person Y. I am not claiming a one-to-one comparison.

Philo's use here does demonstrate that just before and even in Paul's day a fellow Jewish interpreter of Scripture used "didactic" in a way that does not mean "able to teach" (nor "teachable"), nor does "didactic" even imply that the "didactic" one is doing (or receiving) teaching. Do you see the importance of this historical/cultural data? Our debates have bounced back and forth between "able to teach" and "teach-able" and have not even considered the possibility that being "didactic" might not even imply doing teaching at all. But the historical evidence we have that is closest and nearest to Paul demonstrates that the "didactic" one has nothing to do with ability and is not even doing teaching.

So, I suggest:

1. we translate didaktikos as "didactic" (not "able to teach"); and

2. this has to do generally with being associated with or characterized by or oriented toward

teaching that is not necessarily one's own.

Begin to think of Paul's context now. Suppose Person X is teaching something to Person Y. Along comes Person Z who over-sees or super-vises (epi-skopein) Person X teaching Person Y. Paul does not label the teacher or the student "didactic." Paul takes a third option, calling Person Z "didactic." Why? Because the overseer, Person Z, has a character that is associated with or characterized by or oriented toward teaching, even though it is not his own teaching. This plays out practically in some key associated Pauline texts and in Adroa's (and our) contexts.

5. Some Applications Regarding Being a "Didactic" Overseer or Elder or Pastor in the Ancient and Current Global Church

The understanding of "didactic" above fits Pauline communities well. On the one hand, Paul delights in varieties of teaching being done throughout all sectors of Christ's communities of faith. Remember, all saints are to "teach" and counsel each other in some sense; Christ particularly gifts some in "teaching"; Christ even gives "teachers" to the church more as an identity or role (see §2.1).[41] Do you realize there is no evidence that any of those whom Christ Spiritually gifts in "teaching" or establishes as "teachers" must be or even are the overseers/elders/pastors? (Though we do know that some of the later Ephesian elders did labor at it.) On the other hand, Paul explicitly pushes overseers/ elders/pastors to rule, lead, direct and care for the saints.

So, practically today, what if you are put forward to be an overseer or elder or pastor but you cannot teach? Or suppose you are considering someone like Adroa as an overseer/elder/pastor even though you know he cannot teach. To be an effective overseer/elder/pastor, what do you need to be—in your character (see §5.1)? And what must you be able to do (see §5.2)?

5.1 Be Overseers With a Didactic Character (1 Tim 3:1–7)

Since commentators tend to take "didactic" as "able to teach" in 1 Tim 3:2, they say it's the only ability, skill, gift, duty, or competency provided in a list otherwise full of character qualities.[42] It seems to be the odd-man-out.

Starting on that (faulty) footing, it is easy to push further: if "didactic" is unique in the list, perhaps it is divinely meant to stand out. Perhaps we are therefore meant to elevate teaching (often collapsed into "preaching") to prominence in the work-life of the pastor: as if, "The moral character qualities are the obvious, baseline qualifications—really what all Christians should aspire to—so the real question is: can you teach (preach)?"

But that (common) reading is neither correct nor helpful. If I have rightly argued above that (1) we should translate didaktikos as "didactic" (not "able to teach") and (2) we should unpack Paul's meaning as oriented toward the teaching that is happening in the community, even if not doing any oneself, then the following four statements are true:

• In 1 Tim 3:1–3 there are no skills or activities.

• In light of 3:1–3, the overseer needs around twelve character traits and orientations, including having a character that is "didactic" (i.e., oriented toward overseeing the teaching that people are doing in the Christian community).

• In 3:4–5 a task is described for the overseer: not teaching, but leading (i.e., managing, directing, ruling) as a father or household-manager of God's family, the church.

• In 3:6–7 Paul again shifts to qualities rather than skills or even activities.

What do these observations mean for someone like Adroa (or anyone) put forward by their church to be an overseer/elder/pastor?

First, doing the teaching falls to other people in the Christian community, not necessarily to any of the overseers, elders, pastors (certainly not all of them). Remember how ubiquitous and liberally distributed teaching was in Pauline circles (§2 above). Second, the better question regarding Adroa is this: does he show a character of consistent care toward and responsibility for (directing, ruling, leading) what others are teaching so that he actively does something about it, whether positively or negatively? But wait; what does that mean?

5.2 Is He Able to Urge in Someone Else's Teaching (Positively) and to Expose Naysayers (Negatively) (Titus 1:9)

Within Paul's list of qualifications of elders and overseers in Titus 1:9, he gives what many consider the parallel but fuller idea to "didactic" from 1 Tim 3:2.[43] Indeed, it is, though not in the way people have typically thought.

In Titus 1:6–9, Paul paints a picture of the "overseer" or "supervisor" (ton episkopon), whom he had previously called "elders" (presbyterous) in 1:5. They must be "God's house-manager" (theou oikonomon). Thus, they are to function like "a slave placed in charge of a household and acting on behalf of the head (i.e., God)."[44] As such, a church supervisor must necessarily do three things:

(1) cling to the faithful word that accords with the teaching [tou kata tēn didachēn pistou logou], in order that (2) he might be able [dunatos ē] to urge in the teaching that is healthy [parakalein en tē didaskalia tē hygiainousē] and (3) to expose the naysayers [tous antilegontas elegchein] (Titus 1:9).

The word "teaching" is present in Paul's statement in Titus 1:9, twice. (Still more in the immediate context; see below.) Neither instance is directly connected to the overseer's ability or even activity of teaching. "Urging" must be his ability and activity.

First, the overseer must (1) cling to the faithful word that accords with the teaching, most likely the apostolic [45] (which itself accords with the OT and the gospel). Second, a church supervisor must be able "to urge" (parakalein), to encourage or implore, "urging one to accept" the healthy teaching[46] "and [to] respond appropriately to it."[47] The overseer/elder must also be able "to expose" (elegchein), to prove something false "by cross-examination and counterevidence"[48]—exposing those speaking against the healthy teaching.[49]

Look at the context. Four people or groups of people are mentioned as actively teaching—none of whom are the overseers/elders:

1. the apostles' teaching[50] is "the basis on which an overseer may be able to accomplish" his tasks of urging in the teaching and exposing those who oppose the teaching (1:9a);[51]

2. those opposing the healthy teaching are also "teaching things they ought not" (1:11), and the overseers must severely expose and rebuke them (1:9, 13);

3. due to the presence of false teachers, Titus himself must "speak what is proper in the healthy teaching" (2:1), and "in your teaching show integrity and dignity" (2:7);

4. and older women must continue their own "good teaching" and training of younger women (2:3–4) while Titus must "urge" them in their teaching just as he must "likewise urge" (hōsautōs parakalei) the young men in things suitable to them (2:6).

Paul thus gives evidence of various types of people in the Christian community on Crete actively "teaching," none of which are overseers/elders (pastors).

But those overseers/elders in Crete (and beyond; this passage is prescriptive, not merely descriptive) do have a definite task related to teaching that is going on. In this context, the overseers/elders (pastors) must be

• able to urge people in the apostolic teaching;

• able to urge people in Titus's teaching (I presume);

• able to urge young women in the old women's teaching (or urge the old women to continue

in their own good teaching);

• able to expose those who are opposing the good teaching and rebuke them when teaching

what is not good and true.

How might we summarize the characters of these overseers/elders (pastors) in Titus 1, which is in line with 1 Tim 3? Not least, they must have "didactic" characters that are deeply associated with or characterized by or oriented toward overseeing the teaching—the good and the bad—that is going on in the Christian community (none of which is necessarily their own).

Practically, then, reconsider Adroa. He is not a gifted teacher. He is actually a confusing teacher. But he does not need to teach. Is he able to urge people in the apostolic teaching that various saints (like the old women) are doing within the community of faith? Is he able to expose people who are coming against those within the community who are providing healthy and good teaching to various sectors of the church? Is he able to rebuke those who are teaching falsely? If Adroa is committed to such urging and exposing, he clearly has a "didactic" character even though he is not personally able to teach nor even doing any teaching himself.

6. Conclusion

The church around the world needs such didactic overseers of the teaching that is going on. Please do not demand that a didactic overseer/elder/pastor personally teaches or is even able to teach. It is not a biblical qualification.

Rather, encourage all the saints to teach and counsel each other in Christ. Encourage the gifted "teachers" throughout the church to do what God wants them to do—teach—even if none of them are your overseers, elders, and pastors.

Do not worry if Christ has not gifted any of your overseers/elders/pastors with skills or even an ability to teach. It is Christ's prerogative whom he gifts with what, and "teaching" is not actually within the overseer's/elder's/pastor's qualifications or "job description" (so to speak). Do not be confused here: Christ does give teachers to the church. Christ does supply the need. But Christ does not promise that those gifted in teaching will be your church's overseers/elders/pastors. No, Christ creates a body with different parts who each use their particular skills in relation to others to build up the church to maturity in Christ.

Finally, if you appoint overseers/elders/pastors wisely and biblically, then they (like Adroa) will didactically oversee and supervise the teaching that those whom Christ calls and equips to teach will do. Your overseers/elders/pastors will protect the sheep by exposing and rebuking the naysayers and false teachers. And they will feed the sheep by urging the flock in the good, healthy, and beautiful teaching that is going on.

[1] In this article, I will assume the same perspective. Such ecclesial definitions will affect the application of the insights of this article, but they do not affect the argument regarding what it means for an overseer to be "didactic" in 1 Tim 3:2.

[2] Throughout this article, I intentionally use slightly awkward phrases such as "doing teaching."

[3] See Jonathan Worthington, "Mature Together: The Task of Teaching in Missions," Desiring God, March 22, 2022, https://www.desiringgod.org/articles/mature-together.

[4] I. Howard Marshall, The Pastoral Epistles (London: T&T Clark, 1999), 176.

[5] I assume that Priscilla and Aquila, who lived in Ephesus for years, would have agreed with what Paul writes to Timothy in Ephesus in 1 Tim 2:11–12 and thus worked together to carefully arrange the setting of her teaching of men like Apollos so as to maintain propriety.

[6] Paul was not functioning with the type of systematic precision we often crave. E.g., he writes about apostles, prophets, and teachers more like a role than a gift in 1 Cor 12:28–29, but he transitions to gifts seamlessly in 12:29–31. Similarly, Paul's language of "prophecy" throughout 1 Cor 13–14 sounds more like gift-language than role-language, and in 14:6 Paul writes of speaking . . . in prophecy, or in teaching—making no distinction between gift-language and what he formerly wrote in role-language.

[7] The italicized language above captures Paul's oft-misunderstood A-S-K-S (article-substantive-kai-substantive) grammar with plural nouns in Eph. 4:11. See Jonathan Worthington, "Navigating the Pastors and Teachers in Ephesians 4:11," Themelios (forthcoming).

[8] Some commentators mention it is "possible" (though not necessarily favorable) to translate malista ("especially") as "that is," which would imply that the way to "lead well" is by laboring in word and teaching: e.g., Philip Towner, The Letters to Timothy and Titus (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2006), 125; William Mounce, Pastoral Epistles (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2000), 306; Marshall, Pastoral Epistles, 612. Interestingly, each commentator refers for proof to this article: T.C. Skeat, "'Especially the Parchments': A Note on 2 Timothy IV.13," The Journal of Theological Studies 30.1 (1979): 173–77. But Skeat launches his article with confessed inability to picture how Paul might want additional "books" to the parchments that he "especially" wants: i.e., if he wants some, how can he especially want others? I find this natural to imagine. Skeat then suggests "that is" would make more sense than "especially," and he begins exploring data in the NT and in some second and third century Greco-Roman letters that he believes make more sense with malista as "that is" rather than its normal "especially." In my reading, every instance Skeat posits actually makes better sense with the more established and widespread "especially" or "particularly."

[9] See Worthington, "Navigating the Pastors and Teachers."

[10] Claire S. Smith, Pauline Communities As "Scholastic Communities": A Study of the Vocabulary of "Teaching" in 1 Corinthians, 1 and 2 Timothy, and Titus, WUNT 2.335 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2012).

[11] So too must be the Lord's slave (2 Tim 2:24).

[12] See Ralph Earle, Word Meanings in the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1991): "The meaning is 'skillful in teaching.' It may be rendered 'able to teach'" (390).

[13] In 2 Tim 2:2, Paul uses slightly different language to tell Timothy to entrust to "faithful people" what he heard publicly from Paul—those "who will be sufficient [hikanoi] also to teach others." Those "faithful people" are not necessarily only pastors, overseers, elders. In the Pastoral Epistles, Paul's pattern is to use anēr when referring specifically to men. On the other hand, every use of anthrōpos in 1 Timothy and Titus (except maybe 1 Tim 6:11) is most likely about humans in general, regardless of gender (1 Tim 2:1, 4, 5; 4:10; 5:26; 6:5, 9, 16; Titus 1:14; 2:11; 3:2, 8, 10). In 2 Timothy, two of the five are clearly referring to generic humans (3:2, 13), one is referring to two men though is still considering them simply as corrupt humans and not just corrupt males (3:8), and "God's human" being equipped by Scripture in 3:17 could be referring to the effect of Scripture on any human belonging to God (though it could also be referring to Timothy in particular, like 1 Tim 6:11 might be). It is likely, then, that Paul's language of "faithful humans" in 2 Tim 2:2 instead of "faithful men" is more general than specifically about males—e.g., Apollos, Priscilla, the nameless many who were teaching, the old women in Crete. See Stanley Porter, The Pastoral Epistles: A Commentary on the Greek Text (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2023), 560; Osvaldo Padilla, The Pastoral Epistles (Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2022), 174n20; Walter Liefeld, The NIV Application Commentary: 1 and 2 Timothy (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1999), 246–47, 246n2; contra George Knight III, The Pastoral Epistles (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1992), 391; Marshall, Pastoral Epistles, 726; Mounce, Pastoral Epistles, 506–7. NB: some readers will be tempted to theologically panic here; others will be tempted to theologically overstretch the data. Notice how "faithful people" who will be sufficient also to teach others does not necessarily imply women doing what Paul disallowed in 1 Tim 2:12, and it can easily and naturally refer to people like the faithful older women in Crete who give "good teaching" to the younger women.

[14] See Paul A. Himes, "Rethinking the Translation of διδακτικός in 1 Tim. 3:2 and 2 Tim. 2:24," The Bible Translator 68.2 (2017): 189–208. As we will see in §4.2 below, when Himes defines didaktikos as "characterized by teaching"—so far so good—he only thinks about doing teaching. That assumption is not necessary and even leads Himes to reject the historical importance of Philo's uses of the term. This weakness in Himes' otherwise solid study is repeated by Porter, Pastoral Epistles, 277.

[15] Christopher Hutson, First and Second Timothy and Titus (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2019), 93.

[16] Mark Joyal, "Education in Greek and Roman Antiquity," in The Oxford Handbook of the History of Education, ed. John Rury and Eileen Tamura (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), 82–97.

[17] A.V. Yannicopoulos, "The Pedagogue in Antiquity," British Journal of Educational Studies 32.2 (1985): 173–79.

[18] Michael Smith, "The Role of the Pedagogue in Galatians," Bibliotheca Sacra 163 (2006): 197–214; Norman Young, "Paidagogos: The Social Setting of a Pauline Metaphor," Novum Testamentum 29 (1987): 150. Cf. Richard Longenecker, "The Pedagogical Nature of the Law in Galatians 3:19–4:7," JETS 25 (1982): 53, though Longenecker downplays the tutoring role too much.

[19] Some have argued that didaktikos should be understood as "teachable." See Ceslas Spicq, Theological Lexicon of the New Testament, translated by J. D. Ernest (Peabody: Hendrickson, 1994), 433; K.H. Rengstorf, "διδακτικός," in Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, ed. G. Kittel, vol. 2 (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1965), 165. Howard Marshall mentions that "the sense 'teachable' is less likely, but is regarded as possible," and cites Philodemus, Rhet. II, p. 22, 10 as well as Philo, Praem. 27; Mut. 83, 88; Cong. 35. Pastoral Epistles, 478. As we will see, "teachable" is not what Philo means in his four uses. Raymond Collins attempts both translations: "the Pastor expresses the desire that the overseer be willing to learn and able to teach (didaktikon, see 2 Tim. 2:24)" (1 & 2 Timothy and Titus [Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2002], 82–83).

[20] Louw and Nida, §33.233.

[21] Liddell, Scott, Jones, 1.421. Luke Timothy Johnson is reserved in wording: "Including this quality may...point to the function of the supervisor as teacher" (The First and Second Letters to Timothy [New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001], 215).

[22] Harold Moulton, The Analytical Greek Lexicon Revised (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1978), 98; Horst Balz and Gerhard Schneider, Exegetical Dictionary of the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1990), 316.

[23] Bauer, Arndt, Gingrich, 191; Danker, 240; Michael Burer and Jeffrey Miller, A New Reader's Lexicon of the Greek New Testament (Grand Rapids: Kregel, 2008), 399.

[24] Frederick William Danker with Kathryn Krug, The Concise Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), 94.

[25] A. Robertson, A Grammar of the Greek New Testament in the Light of Historical Research (Nashville: Broadman, 1934); Andreas Köstenberger, Benjamin Merkle, and Robert Plummer, Going Deeper with New Testament Greek (Nashville: B&H Academic, 2016).

[26] William Chamberlain, An Exegetical Grammar of the Greek New Testament (New York: Macmillan, 1961), 13.

[27] Louw and Nida, §33.233.

[28] See Heinrich von Siebenthal, Ancient Greek Grammar for the Study of the New Testament (Oxford: Peter Lang, 2019), 661.

[29] James Moulton and W.F. Howard, A Grammar of New Testament Greek (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1978), 379.

[30] Chamberlain, Grammar, 13. Cf. Herbert W. Smyth, Greek Grammar (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1920), 237.

[31] Jonathan Worthington, Creation in Paul and Philo, WUNT 2.317 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2011), 180–81.

[32] Smyth, Greek, 237.

[33] Moulton and Howard, Grammar, 379.

[34] Paul Himes, "Rethinking the Translation of διδακτικός in 1 Tim. 3:2 and 2 Tim. 2:24," The Bible Translator 68.2 (2017): 189–208.

[35] For orientation to Philo and his various types of commentaries, see Jonathan Worthington, "Philo (1): Use of the OT," in Dictionary of the New Testament's Use of the Old Testament, eds. G.K. Beale, D.A. Carson, B. Gladd, A. Naselli (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2023), 603–11.

[36] Benjamin Morison, "Sextus Empiricus," The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2019 Edition), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2019/entries/sextus-empiricus/.

[37] Himes, "Rethinking," 198.

[38] Merriam-Webster, ad loc; cf. Oxford English Dictionary, ad loc.

[39] Collins misunderstands Philo's use of didaktikos, suggesting that "Philo relates ability to teach with leadership and the acquisition of virtue" (1 & 2 Timothy and Titus, 83, emphasis mine), importing a specific interpretation of 1 Tim 3:2 into Philo's term.

[40] See also Philo's On Rewards and Punishments 27, which is Philo's more systematic rather than verse-by-verse treatment of various OT laws.

[41] See Worthington, "Navigating the Pastors and Teachers."

[42] Porter, Pastoral Epistles, 277; David Ackerman, 1 & 2 Timothy/Titus (Kansas City: Beacon Hill, 2016), 134; Towner, Letters to Timothy and Titus, 252; Mounce, Pastoral Epistles, 174; Marshall, Pastoral Epistles, 478; Gordon Fee, 1 and 2 Timothy, Titus (Peabody: Hendrickson, 1988), 81. Cf. Korinna Zamfir, "Once More About the Origins and Background of the New Testament Episkopos," Sacra Scripta 10.2 (2012), 202–22, who calls it the only "explicit competency" on p. 218. For the sense that 2 Tim 2:2 shows that the "skill" of "ability to teach" is "apparently not exclusively" associated "with the task of the overseer," see Towner, Letters to Timothy and Titus, 252; Marshall, Pastoral Epistles, 478.

[43] Knight, Pastoral Epistles, 159; cf. 155–60, 294; Porter, Pastoral Epistles, 743; cf. Mounce, Pastoral Epistles, 392. This text usually shows up parenthetically after mention of 1 Tim 3:2: see, e.g., Robert Yarbrough, The Letters to Timothy and Titus (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2018), 197; Marshall, Pastoral Epistles, 165–67. Marshall uses circular exegetical reasoning: Titus 1:9 interprets 1 Tim 3:2 by giving "a fuller form of the brief and general didaktikos in 1 Tim. 3:2" (165) while "the assumption" that "the overseer preaches and teaches (as explicitly in 1 Tim. 3:2)" interprets Titus 1:9 (166).

[44] Marshall, Pastoral Epistles, 175; cf. F. Young, The Theology of the Pastoral Letters (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 102–3.

[45] Hutson, First and Second Timothy and Titus, 219.

[46] Some have taken en ("in") in an instrumental way (Quinn, The Letter to Titus [New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990], 93), i.e., as the means to do the urging: urge by teaching what is healthy (Perkins, Pastoral Epistles, 251; cf. Andreas Köstenberger, 1–2 Timothy & Titus [Nashville: Holman, 2017], 315; Ackerman, 1 & 2 Timothy/Titus, 406–7; Fee, 1 and 2 Timothy, Titus, 175). Porter disagrees, saying that the "encouragement occur[s] within the sphere or realm of sound teaching" (Pastoral Epistles, 742n41; cf. Marshall, Pastoral Epistles, 167; Knight, Pastoral Epistles, 294). I think something like sphere makes better sense than instrument, especially in light of the practicalities in this context (see below).

[47] Knight, Pastoral Epistles, 294.

[48] Hutson, First and Second Timothy and Titus , 219.

[49] In Titus 1:9 Paul differentiates between "urging" and "exposing," on the one hand, and "in the teaching" in which they are supposed to urge or expose naysayers on the other hand. This implies that in this context Paul does not see the "urging" and "exposing" as themselves "teaching" activities, even though they certainly involve communication of truth. Remember, do not attempt to find a way to make all types of communication "teaching." We are exploring what Paul meant by "teaching," and here he differentiates it from urging in the teaching and exposing naysayers.

[50] Yarbrough, Letters to Timothy and Titus, 489; Knight, Pastoral Epistles, 293; Mounce, Pastoral Epistles, 391–92. For a list of alternatives to this apostolic reading of "the teaching" in Titus 1:9 see Porter, Pastoral Epistles, 741, though Porter himself supports apostolic (at least Paul's) teaching.

[51] Knight, Pastoral Epistles, 293.